Performing with accurate vertical rhythmic alignment or “playing in time” is a subject worth addressing in any style of music, but nowhere is it more important or difficult than in marching band. Unusual listening environments and placement of performers leads to complex situations and unique problems, but understanding and applying the following concepts tends to provide simple solutions to even the trickiest scenarios.

Rhythm and meter still apply. This seems obvious, but all too often as instructors or educators we will hear a performance error and assume it is related to the staging (the placement of the performers on the field). It is always worth evaluating the rhythmic accuracy of the performance with a metronome directly behind the players so they can simply listen. If they cannot play accurately with the metronome in this scenario, it is most likely that the performers are playing the rhythm without relating it to the meter, which must be addressed before any other problem can be solved.

Physics is not an opinion. While there are numerous valid opinions on the best way to address timing, I have never encountered a successful one that did not account for the basic physics of how sound travels. Simply put, sound travels in a sphere away from its source at a constant rate of speed, but one that varies depending on the density of the air and is thus affected by temperature, humidity, and altitude. This speed is generally around 343 meters per second, or in marching band terms slightly less than a football field per eighth note at q=120bpm. While this sounds like a complex scenario and there are in fact many variables, once we add the fact that the speed of light is fast enough to be instantaneous for our purposes (~327,360,000 yards per second; if the performers are that far apart I’m pretty sure they’re on the wrong dot if not the wrong planet) we can simplify all our problems to deciding if we should watch a conductor or listen to other performers.

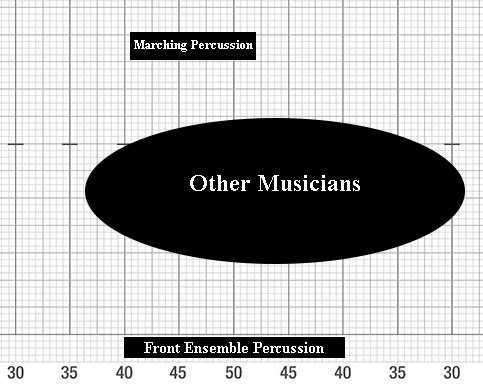

Creating an accurate “pulse tree.” The term “pulse tree” refers to the connection between the initial source of the beat in the music and each individual performer, defining who is listening and watching to whom and when. For instance, the most common scenario has the marching percussion near the back of the group of performers, with a conductor in the front of the field, front ensemble percussion on the front sideline in the center, and the other musicians staged in various places.

In this case, the marching percussion is generally considered the source of the beat because they are the easiest to hear and are placed where many performers can simply listen. In the example above, the front ensemble and any of the musicians directly between the marching percussion and the audience will sound accurate if they listen back and play with what they hear. For the musicians not directly in front of the marching percussion (or “outside the pulse pocket,” in the above example roughly the musicians outside the 40 yard lines), listening will result in sounding late to the audience due to the physics of sound as described above.

To fix this, the conductor must watch the marching percussion using their feet, drum sticks, or some other visual cue to gain a sense of pulse for their conducting pattern, which the musicians outside the pulse pocket will then watch as their source. This uses the speed of light to overcome the problems of the speed of sound, meaning that although the people who are watching instead of listening will perceive that the music sounds incorrect from their perspective, the audience will hear all of the sounds arriving at the correct time. In terms of pulse tree, the field percussion is the source with the musicians in pulse pocket and the front ensemble listening, and the drum major watching the field percussion to provide time visually for the musicians outside the pulse pocket.

While this already may sound complex, there are some simple rules to keep in mind:

- Always listen back, never listen forward, avoid listening to the side.

- If everyone is watching or everyone is listening, the sound will not arrive at the audience together.

- When diagnosing problems, simplify by breaking down the pulse tree into the connections between the pulse and the performer; by definition it is somewhere in the tree or it is a rhythmic error.

It is ok to change the music or the staging. With due respect to my fellow marching band designers, it’s not the Bible and it’s not Bach, so it’s ok to change either the music or the staging if it is too difficult for the performers. At the highest competitive levels of DCI where the performers have the most talent and superlative achievement is expected, it is routine to change one or the other to improve clarity. While most problems are solvable and educationally it is worth trying to teach students how to handle various performance scenarios, this is still definitely worth keeping in mind. Competitively or artistically, there is no particularly good reason to spend large amounts of ensemble rehearsal time on moments that are more difficult than is necessary to create the desired effect for the audience.